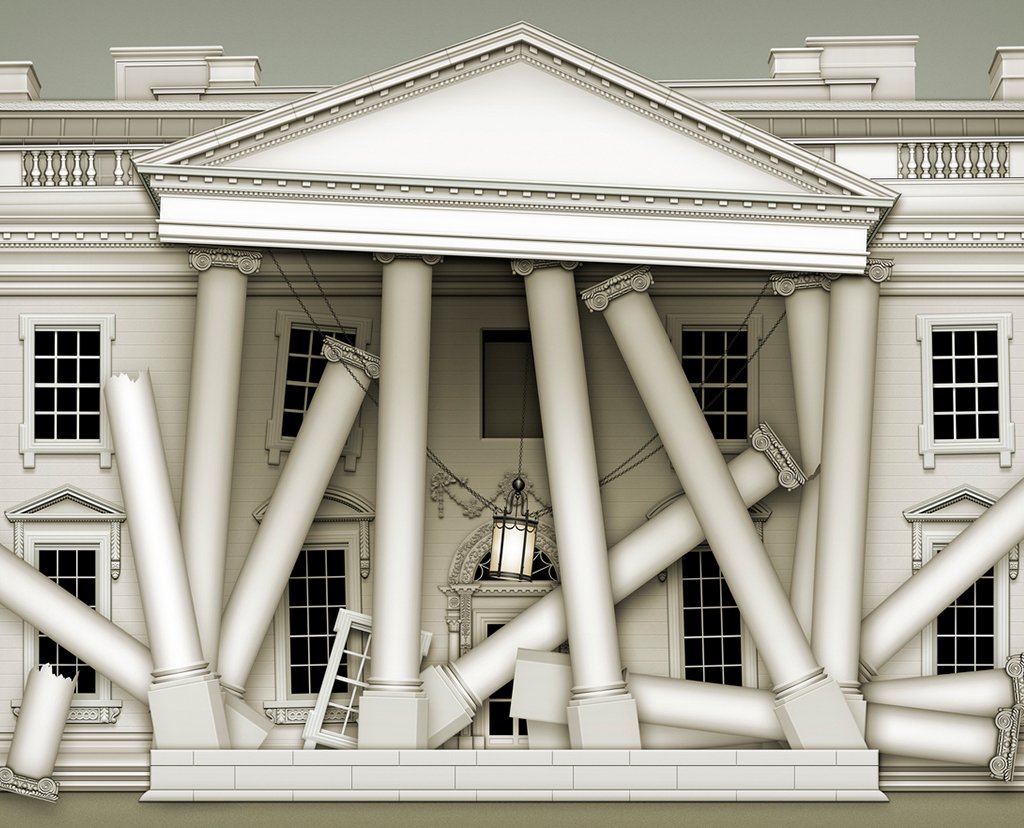

When a President moves into the White House, they are granted a temporary occupation essentially a four‑year “rental” of federal property in trust for the American people. But what happens when that rental begins looking like a permanent lease, and the occupant starts signaling intent to stay in charge indefinitely? President Donald J. Trump’s plan to demolish the East Wing of the White House and build a 90,000‑square‑foot ballroom backed by an Executive Order titled “Making Federal Architecture Beautiful Again” is more than just an ambitious building project. It is an acute reminder that unchecked executive action, especially on the epicenter of the nation, may reflect an underlying ambition to extend power beyond the constitutional bounds of the office. In short, this is not just architecture, it is politics.

The Ballroom Plan and Executive Order

On August 28, 2025, President Trump signed Executive Order Making Federal Architecture Beautiful Again, declaring a preference for “classical architecture” in federal public buildings and directing the General Services Administration (GSA) to revise policies accordingly. Under that order, federal buildings in Washington, D.C., should “uplift and beautify public spaces,” should reflect the “dignity, enterprise, vigor, and stability” of the American government, and in the District of Columbia should default to classical architecture unless exceptional factors apply.

Shortly thereafter, work began on the White House East Wing demolition before formal review by the National Capital Planning Commission. President Trump told donors that he was told “you can start tonight” because as the President he faced “zero zoning conditions.” The private‑donation‑funded ballroom raises deep questions: Whose house is it? Who pays for it? And what powers does the President rely upon to bypass traditional oversight?

Why This Action Goes Beyond Presidential Bounds

Constitutional Limits on Executive Power

Justice Jackson’s concurrence in Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer (343 U.S. 579 (1952)) offers a vital analytical framework:

- Category 1: President acts with Congress’s authorization — power is “at its maximum.”

- Category 2: Congress has neither authorized nor denied the action — the “zone of twilight.”

- Category 3: President acts in a way “incompatible with the express or implied will of Congress” — his power is at its lowest ebb.

President Trump’s ballroom project appears to fall squarely into Category 3: major alteration of federal property in the nation’s capital without congressional authorization, oversight, or appropriation.

The Property Clause & Congressional Authority

Under Article IV, Section 3, Clause 2 of the Constitution, Congress has authority to “dispose of and make all needful Rules and Regulations respecting the Territory or other Property belonging to the United States.” The White House counts as “other Property belonging to the United States,” placing control and oversight authority firmly within Congress’s domain. The demolition and rebuild proposed by President Trump, undertaken absent a clear delegation or congressional act, departs from the Framer’s intent.

Statutory Limits on Executive Residence Alteration

Title 3 U.S.C. § 105 authorizes annual appropriations to the President “for the care, maintenance, repair, alteration, refurnishing, improvement … of the Executive Residence at the White House.” But this statute does not straightforwardly authorize broad demolition or reconstructing wings of the White House, especially without explicit congressional approval of scope, cost, and oversight. The statute says sums “may be expended as the President may determine, notwithstanding the provisions of any other law,” but that language was aimed at operational maintenance, not re‑engineering the White House footprint or evading review.

Article I, Section 9, Clause 7: The Appropriations Clause

The Constitution gives Congress, not the President, exclusive authority to decide how federal money is spent. Article I, Section 9, Clause 7, known as the Appropriations Clause, provides:

“No Money shall be drawn from the Treasury, but in Consequence of Appropriations made by Law; and a regular Statement and Account of the Receipts and Expenditures of all public Money shall be published from time to time.”

This provision is one of the Constitution’s most fundamental checks on executive power. It ensures that every dollar spent by the federal government must be approved by Congress and publicly accounted for. In simple terms, the Appropriations Clause gives Congress control of the purse so that the President cannot spend, allocate, or direct funds without legislative authorization.

The Fifth Circuit reaffirmed this principle in Consumer Financial Protection Bureau v. All American Check Cashing, Inc. (2022), emphasizing that the Appropriations Clause prevents any branch of government from operating without congressional control over its funding. The court explained that this clause traces back to English governance, where the struggle between Parliament and the monarchy centered on the king’s attempts to spend public money without consent. The Framers, fully aware of that abuse, placed spending authority firmly in the hands of the legislative branch to prevent a return to executive financial autonomy.

Even if President Trump claims that his new White House ballroom is funded through private donations, that does not remove it from Congress’s constitutional oversight. Once money, regardless of its source, is used to alter or improve federal property, it falls within Congress’s exclusive authority under the Appropriations Clause. The White House belongs to the American people, not the President, and any substantial structural change to it must be authorized through appropriations made by Congress.

Trump has also invoked Thomas Jefferson as justification for altering the White House. But Jefferson, far from expanding presidential discretion, actually championed stricter limits on executive spending. Id. at 230-231. In an address to Congress, Jefferson urged lawmakers to “multiply[ing] barriers against [the] dissipation [of public monies]” and to ensure that each dollar be tied to a specific, defined purpose. Id. Jefferson’s model of fiscal restraint stands in sharp contrast to Trump’s unilateral decision to demolish and rebuild a section of the White House through privately raised funds, without any congressional oversight.

In effect, Trump’s action revives the very problem the Framers sought to prevent an executive exercising control over federal property and expenditures without legislative approval. The Appropriations Clause is not a procedural technicality; it is a constitutional safeguard designed to keep executive power in check. By proceeding with this project without congressional appropriation, Trump has ignored both constitutional precedent and the fundamental balance of powers the Framers established.

Historic Practice and Constitutional Norms

For more than two centuries, presidents have treated the White House not as personal property but as a mothership for effectuating democratic power, honoring their predecessors and the American people. Renovations to the Executive Residence have historically followed established oversight procedures, even when not legally required. Projects as minor as adding a garden shed or repaving a driveway have gone through public review under the National Capital Planning Commission (NCPC) or the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts. This adherence, while often voluntary, reflected a bipartisan commitment to respect the spirit of the National Historic Preservation Act and the constitutional role of Congress in managing federal property.

President Trump’s decision to unilaterally demolish the East Wing and build a new 90,000 square foot ballroom breaks from this tradition. It goes beyond mere aesthetics. By acting without congressional authorization and financing the project through private donations, Trump is asserting an expansive model of executive power that defies constitutional limits.

This is not just a renovation it is a redefinition of the presidency’s relationship to the federal estate. The White House, a seat of national power, is being rebranded as Trump’s headquarters. Further, if future presidents can privately fund and alter public property without Congress, the presidency begins to resemble the very monarchy that the Framers sought to evade.

Need for Judicial Review

This moment demands judicial scrutiny. A preliminary injunction is a legal instrument courts use to preserve the status quo when there’s a serious constitutional question at stake and continuing the action in question would cause irreparable harm. Here, a preliminary injunction is necessary to halt further construction until the courts can assess:

- Whether President Trump exceeded his authority under the Property Clause of Article IV, which vests Congress not the President with the power to manage federal property.

- Whether this project violates the Appropriations Clause of Article I, Section 9, which requires that no money be spent by the federal government unless Congress has specifically authorized it.

- Whether using private funds to alter federal property amounts to an unconstitutional circumvention of Congress’s exclusive spending power.

These questions underscore the increased instances of separation of powers issues. The issue is not just architectural; it is an unprecedented exercise of executive power. Allowing a president to transform the White House without legislative consent risks invites a slippery slope, where the boundaries between public office and personal dominion dissolve. Until these constitutional concerns are resolved, the construction must stop. The Constitution not individual presidents must determine how the people’s house is governed.

Please subscribe to this blog to receive email alerts when new posts go up.